History of the Toronto, Hamilton & Buffalo

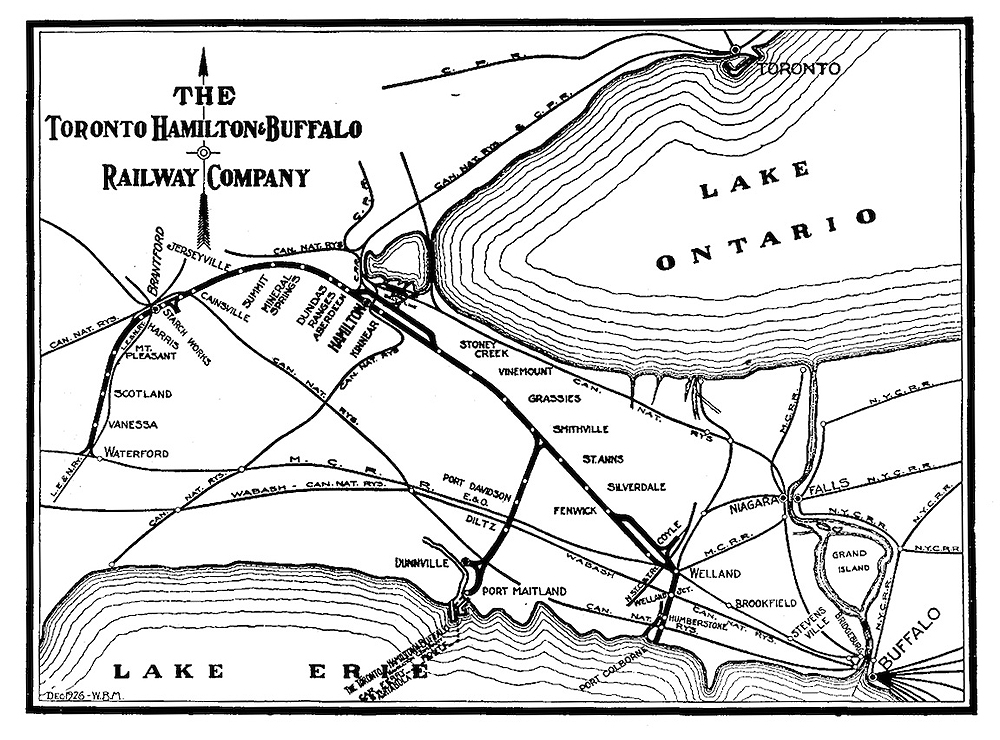

Canada, thanks to its two transcontinental giants after 1923, had few small “regional” railroads. One, though, was the 111-mile Toronto, Hamilton & Buffalo Railway, which vanished in 1987.

Little TH&B had a larger-than-life presence that belied the reality of its being merely the southern Ontario stepchild that linked parents New York Central and Canadian Pacific. TH&B never realized its dream of being an independent road linking its three namesake cities, but in its heyday, it did haul sleeping cars from Toronto for New York, Boston, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, and Philadelphia. In 1911, it became the first North American railroad to install Absolute Permissive Block signaling; it erected a splendid art deco station and office tower in Hamilton, Ontario; and it had Canada’s only 2-8-4 steam locomotives, not to mention two ex-NYC Hudsons.

In 1890, even before a rail was laid, TH&B deviated from its chartered intentions, dropping Buffalo from its plans in favor of an eastern terminus and connection with the Canada Southern, a subsidiary of NYC’s Michigan Central, at Welland, Ontario. In 1892, TH&B acquired its first operating trackage, the faltering 18-mile Brantford, Waterloo & Lake Erie, a Brantford–Waterford line that was extending itself to Hamilton.

Vanderbilt and Van Horne get control

As crews spiked TH&B rails from Hamilton to Welland, the line’s strategic importance attracted suitors. And not just anyone, for on July 9, 1895, the still-incomplete railway was sold to a consortium headed by two of the most powerful men in North American railroading: NYC’s Cornelius Vanderbilt and CPR’s William Van Horne.

NYC, dividing its holdings with subsidiaries MC and CASO, took a 73% stake in the fledgling bridge line; CP held the remaining 27%, an arrangement that would endure for 80-plus years. TH&B was afforded a considerable measure of autonomy, but parental influence from New York and Montreal gave TH&B its unique international character.

The four owners agreed to funnel their bridge traffic and connecting passenger trade over TH&B, but even as the first passenger train left Hamilton for Welland on Dec. 30, 1895, a key piece of the puzzle was missing: the railway had no way to Toronto.

Access to Toronto

CP rode to the rescue in April 1896, negotiating trackage rights over Grand Trunk for 37 miles from Toronto to Hamilton. Instead of fighting GT and bearing the burden of building a parallel line to Toronto, TH&B needed only to build a 1.2-mile link between its line and the GT main through Hamilton. By 1897, the connection was complete, and through Toronto–Buffalo passenger service began.

At first, CP, TH&B, and MC engines handled the passenger trains over home-road trackage, but by 1905, TH&B and MC were pooling power Hamilton–Buffalo. In 1912, CP joined in, and the six daily Toronto–Buffalo trains were handled by a triumvirate that saw NYC-family engines going to Toronto, CP power in Buffalo, and TH&B locomotives going both directions from Hamilton.

TH&B’s fortunes, though, were tied to tonnage, and not just the lucrative bridge traffic for which it was built, but originating freight, much of it from Hamilton. Construction of the Belt Line loop in 1900, followed by the Short Belt Line and Grasselli Branch in 1911, gave TH&B direct access to Hamilton’s burgeoning industrial lakefront. TH&B also secured freight rights on interurban Hamilton & Dundas in 1897, and bought the line outright in 1923.

New century, new direction

The new century brought TH&B a new direction, when in 1914 it took over the 14-mile Erie & Ontario, which went south from Smithville to Dunnville. The major impetus for its construction had been Dunnville’s desire to break GT’s monopoly on local freight, but TH&B’s sights were fixed on Port Maitland, 5 miles farther south, on Lake Erie. TH&B was not as concerned about competing with GT for local traffic as it was about establishing a Lake Erie carferry service.

Toronto, Hamilton & Buffalo Navigation Co. Maitland No. 1, a 2,751-ton steamship with capacity for 32 cars, was launched in mid-1916. On November 1 she went to work for TH&B, departing the NYC docks in Ashtabula, Ohio, with loaded coal cars billed to Hamilton steel mills.

Maitland No. 1 did a respectable trade — heavy on coal for Hamilton and newsprint for U.S. markets — but the service was short-lived. The market crash of 1929 and pending expansion of the Welland Canal convinced TH&B to withdraw from the cross-lake trade, and the boat made her last voyage under the TH&B flag on June 28, 1932, just weeks before the enlarged canal opened. She then ferried autos across Lake Michigan during 1935–37, before giving up her engines for the war effort in 1942 and being cut down for use as a barge.

TH&B motive power

The TH&B locomotives that met the Maitland No. 1 at the slip were not nearly as state-of-the-art. As World War I began, TH&B still operated 4-4-0s, secondhand 0-4-0s from Chicago’s Union Stockyards & Transit Co., and three Moguls built for (and rejected by) the Santa Fe in 1894. Ten-Wheelers and one Pacific were the pride of the passenger pool, and the biggest freight engines were seven 55-inch-drivered 2-8-0s.

After the 1923 delivery of 4-6-2s Nos. 15 and 16, the largest and last locomotives built to TH&B design, the line addressed the need for bigger, faster freight engines for its hot CP-NYC overhead traffic. The first serious road trials were conducted in July 1927 with leased NYC H-10b Mikado 355, but when a brand-new Boston & Albany 2-8-4 hit the property in September, TH&B knew it had its locomotive.

The Lima Berkshire could march up the 1.04 percent climb to Vinemount with twice the tonnage allotted to a Consolidation. TH&B Motive Power Superintendent W. T. Kuhn quickly inked specs for two Berks to call his own.

TH&B As-class 2-8-4s 201 and 202, patterned after Chicago & North Western engines built by Alco in 1927 (customs duties made Lima-built copies of B&A 2-8-4s prohibitive), arrived from Alco affiliate Montreal Locomotive Works in July 1928. They would be Canada’s only Berkshires, TH&B’s first taste of Super Power, and its last new steam locomotives.

The Berks worked the hot Starlight night freight between Hamilton and CASO’s Victoria Yard in Fort Erie (redirected in 1931 to MC’s Montrose Yard in Niagara Falls, Ontario) for their entire careers, although MC crews were known to employ them on transfer runs over Suspension Bridge to the American side during their Montrose layover.

By World War II’s end, TH&B needed a passenger engine to match the Berks’ performance, because its Pacifics, the youngest over 20 years old, were tired. In January 1948, NYC sent help: 18-year-old J-1d Hudsons 5311 and 5313. They became TH&B 501–502 and joined the Toronto–Buffalo passenger pool.

Diesels arrive

Even as TH&B men prepared the Hudsons for service, the line’s first diesels were going to work: NW2 switchers 51–54 from La Grange, Ill. These goats were not TH&B’s first internal-combustion power, for since 1927 gas-electric 301, a 60-foot EMC car built under license by Canadian Car & Foundry, had operated on a rigorous international circuit. Starting from Buffalo in early morning, the little car ran to Hamilton and on to Waterford, where it connected with an MC local to Detroit and Chicago, then returned to Hamilton and Buffalo. The routine lasted until 1954.

In August 1950, TH&B began dieselization in earnest as GP7s 71 and 72 emerged as the first units built at the new General Motors plant in London, Ontario. By year end, two more London GP7s and SW9s 55–58 had TH&B steam on the ropes. Delivery of GP7s 75–77 in summer 1953 dieselized TH&B freights, and steam-boiler-equipped GP9s 401–403 finished off TH&B steam in spring 1954. (Interestingly, the 70s operated short-hood-forward, but the 400s long-hood-forward, as on NYC.) On March 22, 1954, Hudson 501 became the last TH&B locomotive under steam, working east to Toronto on train 722 and returning on 821. Sister NYC 5374 worked trains 792 and 821 the same day to end all steam on the run.

The glory days of TH&B passenger trains also were numbered. By the 1960s, the only train left through Hamilton’s Hunter Street station was the overnight Toronto–Buffalo–New York City Ontarian. TH&B’s three passenger Geeps were bumped to freight, and NYC and CP diesels handled the Ontarian. In October 1970, the train was replaced by CP RDCs on a daylight turn to Buffalo. TH&B went freight-only in April 1981, when VIA Rail Canada canceled the run in favor of its Niagara Falls trains on CN.

Otherwise, TH&B was remarkably stable from the end of steam through the 1970s, settling in a comfortable routine as Geeps worked wayfreights from Hamilton to Brantford and Waterford, and to Welland and Port Maitland. The switchers patrolled the Belt Line and industrial tracks of Hamilton, built trains at Aberdeen Yard and Kinnear, and worked the old H&D to Dundas and on CN rights between Welland and Port Colborne. TH&B Geeps pooled with NYC (and later, Penn Central) sisters on the nightly road freight from Buffalo to the CP yard in Toronto.

Except for the loss of GP7 71, wrecked and burned in a fatal crossing collision in 1980, the TH&B roster remained unchanged. The original units that killed off TH&B steam stayed in service through the mid-1980s, working home rails and carrying the same colors and numbers they’d worn since birth.

Conrail, ordered to divest itself of PC’s interest in TH&B, sold its stake to CP on April 19, 1977, but the little line continued to enjoy autonomy for another decade. In January 1987, CP finally lowered the flag, integrating TH&B into its London Division. That same year, the switchers were sold and the Geeps sent to CP’s Angus shops, where they were chop-nosed and rebuilt as CP 1600s.

Today, TH&B’s seven-story Hunter Street station/headquarters in Hamilton, restored to its 1933 art deco splendor, serves GO Transit passengers and city bus riders. The Belt Line still taps Hamilton’s industrial heart, and rails still extend to Lake Erie at Port Maitland. Moreover, hot international freights still pound over the little piece of Canadian Pacific still known to many as the TH&B, exceeding its founders’ dreams of a bridge line linking the three namesake cities.

A long history for a small railroad that made itself useful interchanging traffic between some major railroads. Well done.

Edward Stoebenau. Obviously not

I worked for CP in the Detroit Sales & Marketing office from 1973 to 1976 as a rate analyst and car distributor. I remember the TH&B very well and suggested TH&B routing to many Detroit area shippers. I welcomed this story, especially because I never knew what happened to the TH&B after the mid-1980’s.

Do you have any proof-reader?

Toronto, Buffalo & Hamilton?

We moved to Hamilton in 1950 one short block from the TH&B near the Kinnear Yard. We could stand in the street in front of our house and watch the trains. My friends and I would regularly cross the tracks to play in the woods of the Hamilton ‘Mountain’ (the Niagara Escarpment). The CNR branch to Hagersville climbed the escarpment about 50-75 yards above the TH&B at this point. While we couldThe TH&B and the CPR were always my favorite Railroads.

I grew up in Hamilton, having arrived from the UK in 1954. The TH&B was a big part of the local scene, as we lived close to the Aberdeen yard.

I grew up in Hamilton and our house was about a half mile from Aberdeen Yard. I remember that the “doodlebug” would go by between 8 to 9 AM and return between 1 and 2 PM. THE Dundas turn would be between 12 and 1PM returning around 4 to 5 PM. Around midnight there would be another train but don’t know if it was in or out of Aberdeen Yard.

Its nick name was ‘To Hell and Back’

Why no steam photos?

While it’s a shame that the road’s name is out of order in the title (as I write), this is a worthy article about an unsung, overlooked, interesting railroad.