R. S. Plummer

History of the Texas & Pacific

What grew to become the 20th century’s Texas & Pacific Railway sprouted from some of Texas’s earliest railroads. The Lone Star State’s pre-Civil War network included 11 operating companies. One of the earliest was the Texas Western Railroad, chartered in 1850 and soon renamed Vicksburg & El Paso. In 1856 its name changed again, to Southern Pacific Railroad Company. Of course, this SP had no relation to the Southern Pacific incorporated in 1865 in California, although the convoluted histories of their successors later would intersect.

Backers of this railroad envisioned it as part of a southern transcontinental route from the Mississippi River to San Diego. By 1860, construction of 27 miles was completed between Waskom, on the Louisiana border, and Marshall. The eastern connection was planned as the Vicksburg, Shreveport & Pacific, which already stretched from Waskom across Louisiana to the west bank of the Mississippi at Vicksburg (later part of Illinois Central, it is now part of Kansas City Southern’s “Meridian Speedway”).

The Memphis, El Paso & Pacific, chartered in 1856, planned to start at the Red River near Texarkana and build to a connection with the SP near Dallas, thereby bringing Midwestern traffic into the transcontinental route. Little progress was made before the Civil War, however, with only 5 miles of track built, near Jefferson.

Within a decade after the war, these two lines would be fused into one company. In 1870 the Memphis road was renamed Southern Transcontinental Railroad, and in 1872 Congress issued a charter for the Texas & Pacific Railway, which soon acquired both the ST and SP. The new charter approved a route from Marshall to El Paso and San Diego, and required 100 consecutive miles of construction by 1882. Backers hired Gen. Grenville Dodge, who had been chief engineer of Union Pacific’s recently completed transcontinental line to Utah.

250 miles in 10 months

Work on the T&P began at three points in early 1873 and, within 10 months, 250 miles of new line had been laid: Longview-Dallas, Paris-Sherman, and Marshall-Texarkana. These pieces connected with the two segments built earlier, giving the T&P a strong network in northeast Texas. These successes were abruptly halted, however, by the Panic of 1873 that forced the line’s construction firm into receivership in 1875.

One of its last projects was the 1874 Trinity River bridge in Dallas to handle the massive livestock traffic originating on the many ranches to the west. Nearby Fort Worth, a big livestock marketing center, became increasingly dissatisfied with the lack of a T&P connection. Frustrated with the cash-strapped railroad, farmers and stockmen organized and graded the 30-mile stretch between the two cities and laid down ties, allowing the first T&P train to enter “Cowtown, Texas” in July 1876.

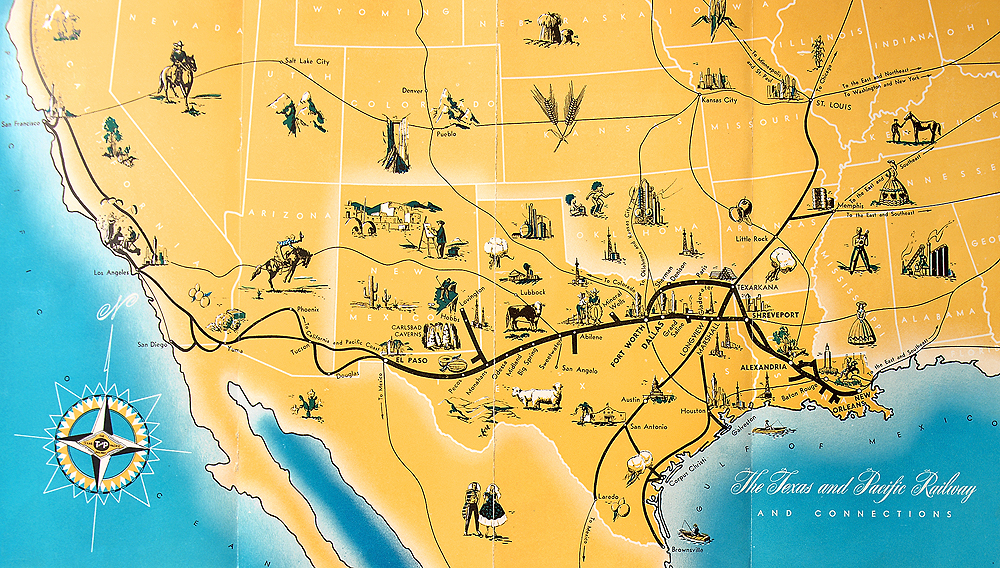

T&P’s western terminus remained in Fort Worth for a few years because of a lack of financial backing. But with its extensive trackage, it was growing rapidly as a transportation enterprise owing to its strategic importance in northeast Texas and its connections through Texarkana and Shreveport to major cities such as St. Louis, New Orleans, and Atlanta. It is ironic that Fort Worth, which had to pay to get into the T&P family, eventually became the operating hub for the system.

Although T&P’s board of directors included business and political leaders, and was led by President Thomas Scott (who also held the presidency of the Pennsylvania Railroad, 1874-80), T&P was unable to secure any federal assistance to build through west Texas and on toward California. However, in January 1880 the road’s future would change abruptly with the seating of two new directors, Jay Gould and his associate, Russell Sage.

Gould had just completed, in 1879, his acquisition of the Missouri Pacific system and was looking for new opportunities. When Scott decided to sell his T&P holdings a year later, Gould and Sage snapped them up. Gould became president and immediately formulated an ambitious expansion plan for T&P, which fit perfectly into his MP system, whose St. Louis, Iron Mountain & Southern connected with T&P at Texarkana. One of Gould’s first moves, in 1881, was to build a line north from Fort Worth to Sherman, giving T&P a second route to Texarkana as well as a direct connection at Denison, Texas, with the recently completed Missouri, Kansas & Texas, which Gould had acquired in 1880.

R. P. Meyer; J. David Ingles collection

Jay Gould vs. C.P. Huntington

Meantime, Gould directed Chief Engineer Dodge to begin an all-out effort to lay rails through the vast and nearly uninhabited desert of west Texas. Construction crews reached Big Spring, 267 miles, in April 1881 and Sierra Blanca (522) on December 16, 1881. However, it was at Sierra Blanca where Gould’s dream of a transcontinental railroad evaporated. He had been bested by Collis P. Huntington, another determined and ruthless railroad tycoon. Huntington’s eastward construction crews had passed through Sierra Blanca three weeks earlier, on November 25, en route to their own “last spike” ceremony of the Sunset Route at the Pecos River (west of Del Rio) in January 1883.

Under the banner of the Galveston, Harrisburg & San Antonio, controlled by Huntington and Thomas W. Peirce, construction crews had left El Paso in June 1881. When it was clear that Huntington was winning the race for a transcontinental line, a series of court battles ensued, followed by nefarious delaying tactics (including sabotage) by each construction crew, and finally by personal negotiation between the two principals. Gould’s legal case was based on T&P’s 1870 charter to build to San Diego, whereas Huntington’s Southern Pacific charter allowed him to meet the T&P at the Colorado River (between California and Arizona).

When the T&P (prior to Gould’s takeover) had failed to gain congressional support for its western construction, Huntington said he could build a transcontinental line without any government assistance. Since there was no challenge to this plan at the time, his position was that the original T&P charter was no longer in effect. Although Gould would have settled for joint ownership of the 90 miles west of Sierra Blanca, Huntington was unwilling to budge, and was eventually victorious in the courts. Thus, although T&P maintained yards and other trackage in El Paso, it operated trains west of Sierra Blanca on an 1881 trackage-rights agreement that continued in effect until the 1996 takeover of Southern Pacific by Union Pacific.

After completing its line to the west, T&P turned eastward and completed its own line from Waskom to Shreveport (in lieu of the VS&P line) and, of more importance, pushed on to New Orleans by acquiring short railroads and constructing connecting segments. Other than building and acquiring several feeder lines, the New Orleans-Dallas-El Paso route represented the geographic limits of the T&P, although the Marshall-Texarkana stretch was probably the busiest segment since it was used by both east-west and north-south traffic from connecting MP lines.

Gould’s empire crumbles

Gould’s railroad empire crumbled in the mid-1880s. One by one his roads — Wabash, T&P, MK&T, and International & Great Northern — entered receivership. He was able to maintain MP control of only two, T&P and I&GN (east and south Texas lines) — both critically important to MP operations. The T&P connection was tightened during a 1923 reorganization in which T&P issued preferred stock to MP in exchange for mortgage bonds, giving the parent company more than 50 percent of common stock and all the preferred stock. So, even though its operations were thoroughly integrated with those of its parent, T&P represented a semi-autonomous subsidiary.

Shielded by a state law that required all railroads operating in Texas to have an in-state general office, T&P exhibited “Texas pride” with its own motive-power department and shops (Marshall and Fort Worth), and its own identity on rolling stock. The earliest rendition of the T&P herald was a stylized diamond with the names of its four major terminus cities on the sides (Texarkana, El Paso, Shreveport, New Orleans).

Like many Texas roads, T&P was blessed by the discovery of oil at both ends of the state. The massive east Texas fields around Ranger were opened in 1918, and a few years later the Permian Basin of west Texas (Midland-Odessa) began producing. During World War II, T&P was one of the major originators of oil trains headed to the coasts.

Distinctive motive power

Linn H. Westcott

T&P’s independent-minded motive-power department holds the distinction of ordering the second of Lima’s “Super-Power” steam locomotives of the mid-1920s. Its I-1 class 2-10-4 heavy freight design, first produced in 1925, was named the Texas type. Eventually the road would acquire 70 of these large engines, representing almost 20 percent of its 372 locomotives in 1929. Styling was also important to T&P motive-power people. The road’s larger engines generally carried British-style capped stacks and Elesco feedwater heaters on their smokeboxes (adorned with a diamond herald) and, when needed, air-pump shields on the pilot deck (also with the herald). Most passenger power sparkled with dark-blue boiler jackets, accented with striping on tender sides and running-board skirts.

Along with its parent, T&P began dieselizing after World War II with mainly EMD power: switchers in 1946, E7 passenger units in 1947, and F7 freighters in 1949. The blue-and-white schemes for cab units were similar to MP’s, but yard and road-switcher units wore “Swamp Holly Orange” with black trim. The last GP9s, and GP18s, had a unique blue-and-gray striping, but in the 1960s, MP’s new “Jenks” solid blue began to prevail on the T&P, although the diamond herald was applied to T&P-owned units until trust certificates expired, after which some MP-style “buzzsaw” emblems read “Texas Pacific Lines.”

In 1956, MP began systematic purchases of T&P stock with a goal of 80 percent ownership that would allow consolidated tax returns for the two companies. Ironically, one of the last large blocks of stock included 12,000 shares from the estate of Frank Gould, grandson of the flamboyant tycoon. By 1957, MP owned 77 percent of T&P and there was talk of merger but, on public perception grounds, it was not pursued. However, in 1976 the semi-independent status of T&P was finally brought to an end after a 30-year legal battle for recapitalization of the MP system’s holding company. In the end, the new Missouri Pacific Corp. absorbed its three major railroads, MP, T&P, and Chicago & Eastern Illinois.

In another large slice of irony, the Fort Worth-Sierra Blanca line that represented so much of Jay Gould’s dreams in the 1880s became a key segment in one of the nation’s premier transcontinental routes in 1996 when Union Pacific, after swallowing up MoPac and Western Pacific in 1982, also acquired Southern Pacific. The ex-T&P line between Texarkana and El Paso is an extremely attractive route, as it is almost 250 miles shorter than the competing line using Cotton Belt and Sunset Route lines, thus providing some final vindication for the ghost of Gould over his one-time nemesis.

This article says T&P passenger power was dark blue. Not true, it only got that during 1948-1950 and was returned to its normal gray green boiler color. Only a few passenger engines got that scheme of blue and gray. The article also does not mention the oil fields of east Texas. On its entire Texas routes only the counties of Dallas and Tarrant did not have oil strikes. There was a saying in Texas. “If you want oil, drill on the right of way of the Texas & Pacific.”