Frank Black, Mike Del Vecchio collection

History of the Lehigh & Hudson River Railway

The Lehigh & Hudson River Railway was a bridge route in the most literal sense. For much of its lifetime, New England freight moving via the 6,747-foot-long (including approaches), 212-foot-high Poughkeepsie Bridge over the Hudson River at that New York town was L&HR’s essential lifeblood and key to profitability. On-line agricultural, mineral, manufacturing, and passenger business, important in the early years, became increasingly marginal as time passed.

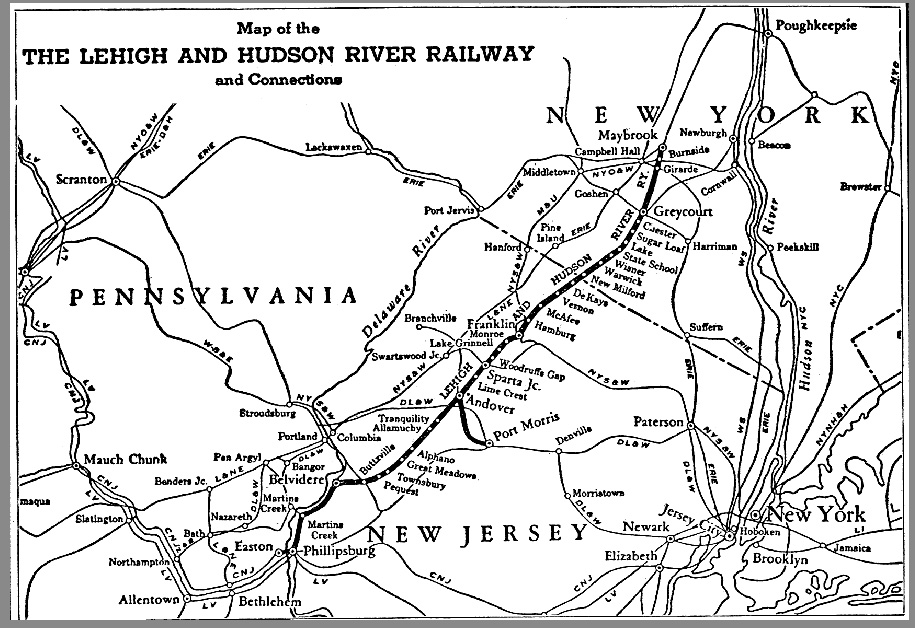

Possessing only 73 route-miles of its own, L&HR had rights on 35 miles of three of its connections: Jersey Central, Lackawanna, and Pennsylvania. L&HR’s own single track was protected by block signals after 1913 and operated under timetable and train-order rules. Operated from headquarters in the rural community of Warwick, New York, L&HR always enjoyed a hometown employee base with a strong sense of local pride, loyalty, and identity. Although short in miles, the railroad was a tenacious competitor to the end and impressive in performance.

Origins in 1860

L&HR’s origins date to 1860, when arrival of the New York & Erie Railroad, at Greycourt, New York, 10 miles north of Warwick, prompted construction of the Warwick Valley Railroad under the leadership of Grinnell Burt. The Warwick Valley operated as a 6-foot-gauge feeder to the same-gauge NY&E, using the big road’s equipment for two decades. Around 1880, WV assumed its own operations, was standard-gauged, and built the 11-mile Wawayanda Railroad, which tapped agricultural and mineral sources at McAfee, New Jersey. Further extension southward soon followed.

Two projected competitive lines were combined as the Lehigh & Hudson River Railroad, extending from a Pennsylvania Railroad connection at Belvidere, New Jersey, on the Delaware River, to Hamburg, New Jersey, where three miles of isolated Sussex Railroad track linked it to the Warwick Valley. In 1882 the extensions were folded into the 61-mile Lehigh & Hudson River Railway.

In addition to the New York & Erie’s mainline business at Greycourt, its Newburgh Branch provided access to Hudson River carferries crossing to the New York & New England’s Fishkill Landing. Anthracite coal, particularly from mines of affiliate Lehigh Coal & Navigation, was a major eastbound commodity. Anticipating completion of the Poughkeepsie Bridge a few miles upstream, the Orange County Railroad built north of Greycourt to connect with the New York, Ontario & Western at Burnside in 1890. Via trackage rights, this provided a first connection with the Central New England & Western at Campbell Hall, New York. Within a year, the Orange County was extended from Burnside to CNE’s new Maybrook yard.

Simultaneously, trackage rights were obtained from the Pennsy over 13 miles of its Belvidere-Delaware Division (“Bel-Del”) to Phillipsburg, New Jersey. There, disconnected subsidiaries undertook bridging the Delaware to access Easton, Pennsylvania, and the Jersey Central and Lehigh Valley. The bridge also opened in 1890, creating a three-state route of about 85 miles. The L&HR thus fulfilled the prescient vision of the line’s 1861 directors, who reported, “It was well understood by those . . . promoting the construction of the Warwick Valley Railroad, that in all probability it would be but a link in a great chain destined to be one of the most important thoroughfares, and to effect an important influence upon the commerce and manufacturers of an extensive section of our country . . .” Additional links soon extended the chain of this “important thoroughfare.”

Donald W. Furler

Connections east and west

When the New Haven acquired the Central New England in 1905, it achieved an all-rail route to western connections at Maybrook. This brought significant traffic, previously floated across New York Harbor, to the L&HR. Especially important was New England freight moving via the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western. L&HR, with trackage rights on DL&W’s Sussex Branch, gained a through connection at Port Morris in 1905, and more priority freight flowed through Maybrook. This formative year also brought rights over the CNJ to Allentown, Pennsylvania, where the Reading provided additional western connections.

L&HR thus achieved a formidable and highly profitable bridge-route status. An additional 30 route-miles were gained briefly in the 1920s when CNJ extended rights to Mauch Chunk (now Jim Thorpe), Pennsylvania, for zinc ore going to a smelter.

Zinc, metallurgical products, and agricultural limestone were the most profitable on-line commodities for L&HR, along with milk shipped from creameries. The Mine Hill Railroad, organized in 1891, reached quarrying operations at Franklin, bringing ore to the processing mill. Additional ore came from the New York, Susquehanna & Western’s Hanford Branch. When this line was abandoned, L&HR bought two miles of it to reach the source. The road had about 100 ore cars to handle this traffic, which were supplemented by Erie cars provided to NYS&W when it was under Erie control. Spurs in McAfee and Vernon reached limestone quarries of Bethlehem Steel and other producers, much of it hauled to Allentown for interchange to the Reading or LV.

L&HR operated through passenger trains for a period beginning with the opening of the Poughkeepsie Bridge and again during 1912–16, when the Boston–Washington Federal Express was avoiding ferrying across the East River. The opening of Hell Gate Bridge moved the Federal back to a metropolitan routing. To handle the train safely and quickly, and for the general improvement of its plant, L&HR upgraded with heavier rail and automatic block signals. Its own passenger service was local, with coach seating sufficient to meet demand. A Brill gas-electric car arrived in 1928 to handle mixed service west of Warwick, but it was destroyed in a grade-crossing collision in 1931. Connections between Warwick and the Erie at Greycourt, using secondhand steel coaches, lasted until 1939.

L&HR locomotives

L&HR motive power was well maintained and notable for the center-cab and wide-firebox influence of its anthracite affiliates. Early locomotive types included 4-4-0s, 2-6-0s, 2-8-0s, and 4-6-0s by Cooke and Baldwin. All 20th century steam came from Baldwin: larger 2-8-0s (six of which were the heaviest of this type); four modest-size, homely 2-8-2s with Wootten fireboxes; four USRA light Mikados; and finally, in 1944, three handsome, modern 4-8-2s, copies of Boston & Maine’s R-1-d class.

Continually expanding heavy-industry, merchandise, and coal traffic found L&HR to be an expeditious route which avoided the congestion of metropolitan yards and interchanges. L&HR kept its physical plant up to the service demand by installing longer sidings, heavier rail, and upgraded signals and maintenance facilities. It was a link in several coordinated freight routes including the Central States Dispatch (CSD) and Blue Ridge Dispatch. In 1950, it replaced 16 steam engines, including the 6-year-old 4-8-2s, with 11 Alco RS3s; two more arrived in 1951. Radio communication came in 1958.

The 1960s began with a centennial celebration including steam-powered excursions with a borrowed Reading 4-8-4, but seismic changes followed. The Erie Lackawanna merger diverted DL&W traffic to the former Erie direct route into Maybrook, a serious but not critical business loss for L&HR. PRR introduced “Trailer Jet” piggyback service between Chicago and Boston routed over L&HR, and additional TOFC traffic for New England came off the Baltimore & Ohio via the Reading and Allentown Yard.

Alco’s first two production C420 diesels arrived in 1963, and seven more by mid-1966 shared assignments with the six remaining RS3s. The Penn Central merger in 1968 created a major threat to L&HR’s traffic patterns because it afforded former PRR traffic an in-house route to Boston over NYC’s Boston & Albany, but it wasn’t until PC’s forced absorption of the New Haven in 1969 that the Selkirk gateway became PC’s preferred route. Dependent as L&HR had been on PRR Maybrook traffic, this was devastating, and the connection was gradually phased out.

J. David Ingles collection

Beset by mergers, bankruptcy, and fire

PC’s bankruptcy in mid-1970, with the cessation of per-diem car payments to connecting roads, was catastrophic to L&HR. It sold most of the remaining RS3s, consolidated trains, and reduced all possible expenses. The road ceased operation into Allentown in late 1971, moving interchange with CNJ and Reading to Phillipsburg. All went for naught, though, and L&HR joined several other northeastern roads in bankruptcy on April 19, 1972.

What would be the final blow occurred in May 1974 when the Poughkeepsie Bridge suffered significant fire damage, providing PC an opportunity to close the Maybrook route to New England. L&HR did its best to force a reopening through political means, even offering its own maintenance force for repairs, but PC was intransigent, and the bridge remained closed. L&HR labor and management cooperated to keep the line running on limited traffic while fighting to collect its traditional rate divisions from PC on detoured traffic.

In 1976 the federal Regional Rail Reorganization Act that created Conrail took in most northeastern bankrupts including L&HR, and CR’s management proved as committed to abandonment of the Maybrook Gateway as PC’s had been. The former L&HR, reduced to a Conrail branch, limped along, bearing slight resemblance to its former proud, busy self as a few of the remaining C420s served a dwindling customer base. Rail movement of zinc ended in 1980, and the track between Limecrest and Belvidere was removed a few years later.

To the credit of its president, W. Gifford Moore, and trustee, John G. Troiano, L&HR paid off its creditors and entrusted its historical records to the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania. Since 1986, the Susquehanna has been operating over the old L&HR between Sparta Junction and the former CR Southern Tier line at Campbell Hall, New York. From the latter point NYS&W had rights over Conrail (now Metro-North and Norfolk Southern) to Binghamton.

PC Arson killed the use of the bridge!